A gentle introduction: BoLD

This introduction is for those who want to learn about BoLD: a new dispute protocol for optimistic Rollups that enables permissionless validation for Arbitrum chains. BoLD stands for Bounded Liquidity Delay and is active on Arbitrum One, Arbitrum Nova, and Arbitrum Sepolia.

What exactly is BoLD?

BoLD upgraded Arbitrum's former dispute protocol. Specifically, BoLD changed some of the rules used by validators to open and resolve disputes about Arbitrum’s state, ensuring that only valid states receive confirmation on an Arbitrum chain’s parent chain (Ethereum).

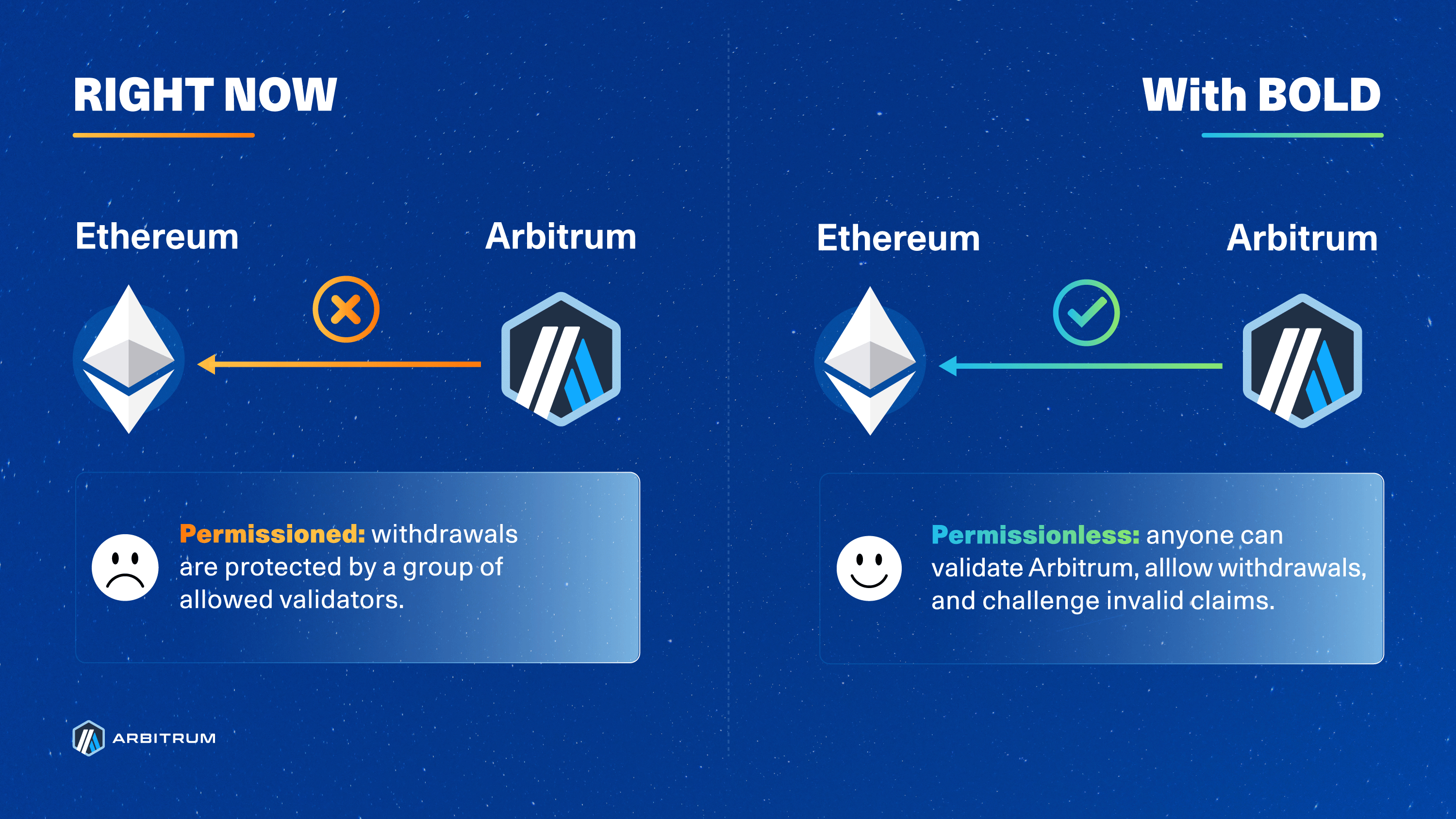

The former dispute protocol leveraged fraud proofs for challenges and was limited to a set of allowlisted validators. BoLD enables anyone to participate in validating the chain state (including challenges) and enhances security around child-to-parent chain messaging (including withdrawals).

Under BoLD, a bonded validator's responsibilities are to:

- Post claims about an Arbitrum chain state to its parent chain (i.e., Ethereum)

- Open challenges to dispute invalid claims made by other validators, and

- Confirm valid claims by participating in and winning challenges

BoLD unlocks permissionless validation, ensuring that disputes are resolved within a fixed period (currently equivalent to two challenge periods, plus a two-day grace period for the Security Council to intervene if necessary, and a small delta for computation), effectively removing the risk of delay attacks and making withdrawals to a parent chain more secure. BoLD accomplished this by introducing a new dispute system that allows any single entity to defend Arbitrum against malicious parties—effectively enabling anyone to validate, propose, and defend Arbitrum's chain state without permission.

Why did Arbitrum need a new dispute protocol?

In the past, working fraud proofs were limited to allowlisted validators, who could assert the state of the chain. BoLD further decentralizes the protocol by allowing anyone to challenge and win disputes, all within a fixed time period. Arbitrum chains will continue to use an interactive proving game between validators and fraud proofs for security, with the added benefit that it is completely permissionless and time-bounded to the same length as a single challenge period (6.4 days by default).

BoLD can uniquely offer time-bound, permissionless validation because a correct state assertion isn't tied to the validator that bonds their capital to a claim. This feature, coupled with the fact that the child chain states are entirely deterministic, can be proven on Ethereum, meaning that any number of honest parties can rely on BoLD to prove that their claim is correct. Lastly, BoLD does not change the fact that only a single honest party is required to defend Arbitrum.

BoLD enables Arbitrum to become a Stage 2 rollup

Inspired by Vitalik’s proposed milestones, the team over at L2BEAT has assembled a widely recognized framework for evaluating the development of Ethereum Rollups. Both Vitalik and the L2BEAT framework refer to the final stage of Rollup development as "Stage 2 - No Training Wheels”. A critical criterion for being considered a Stage 2 Rollup is the ability to allow anyone to validate the child chain state and post fraud proofs to Ethereum without restrictions. This step is a key requirement for Stage 2 because it ensures “that a limited set of entities does not control the system and instead is subject to the collective scrutiny of the entire community”.

BoLD enabled permissionless validation by allowing anyone to challenge incorrect Arbitrum state assertions, unlocking new avenues for participation in securing the network and fostering greater inclusivity and resilience. BoLD achieves this by guaranteeing that a single, honest entity, whose capital is bonded to the correct Arbitrum state assertion, will always prevail against malicious adversaries.

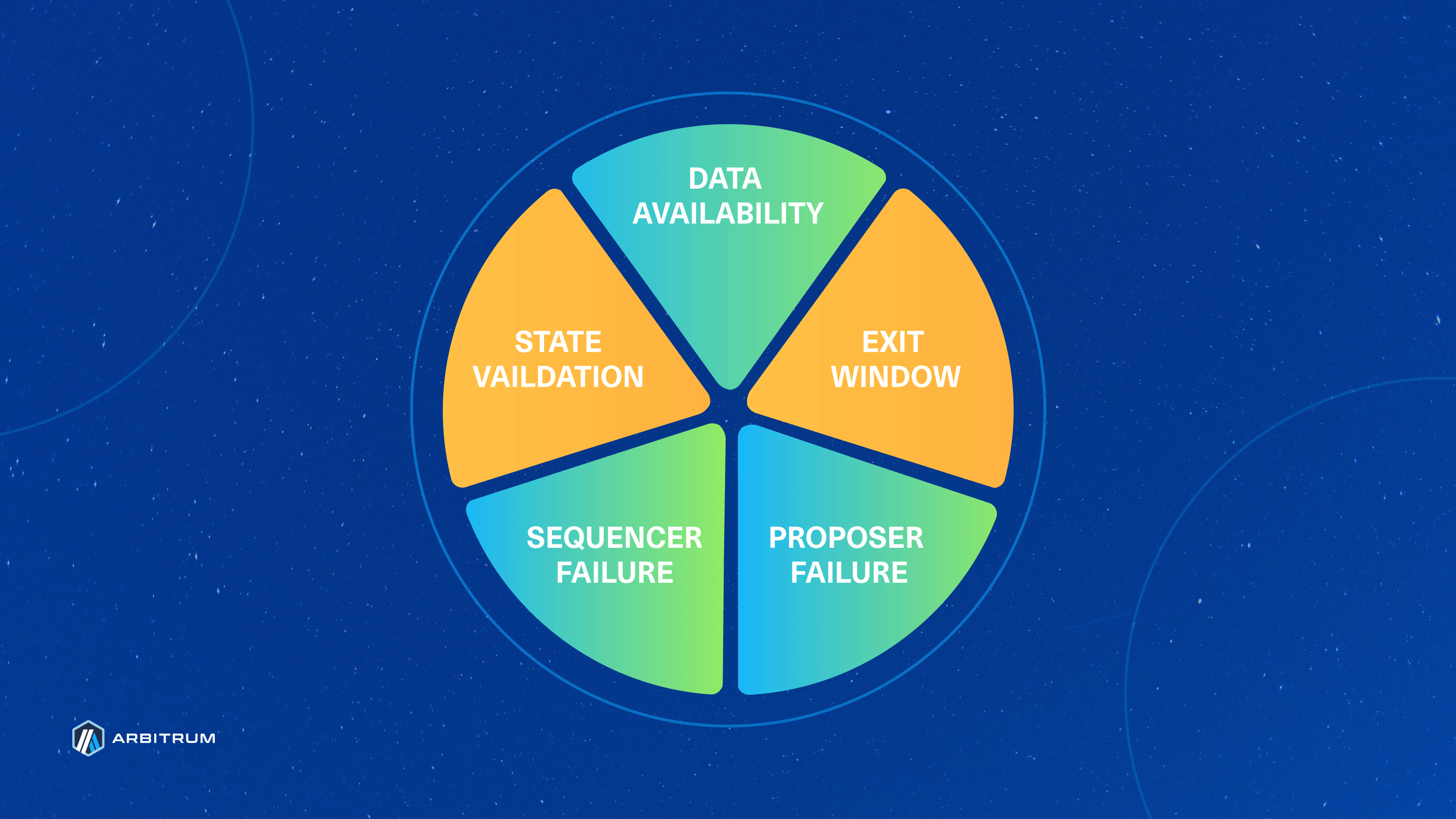

With BoLD at its core, Arbitrum charts a course toward Stage 2 Rollup recognition by addressing the currently yellow (above) State Validation wedge in L2BEAT's risk analysis pie chart. BoLD contributes to a more permissionless, efficient, and robust rollup ecosystem.

BoLD makes withdrawals safer to the parent chain

In the past, there was a period following a state assertion, known as the “challenge period,” during which any validator could open a dispute over the validity of a given child chain state root. If no disputes occurred during the challenge period, the protocol would confirm the state root as valid.

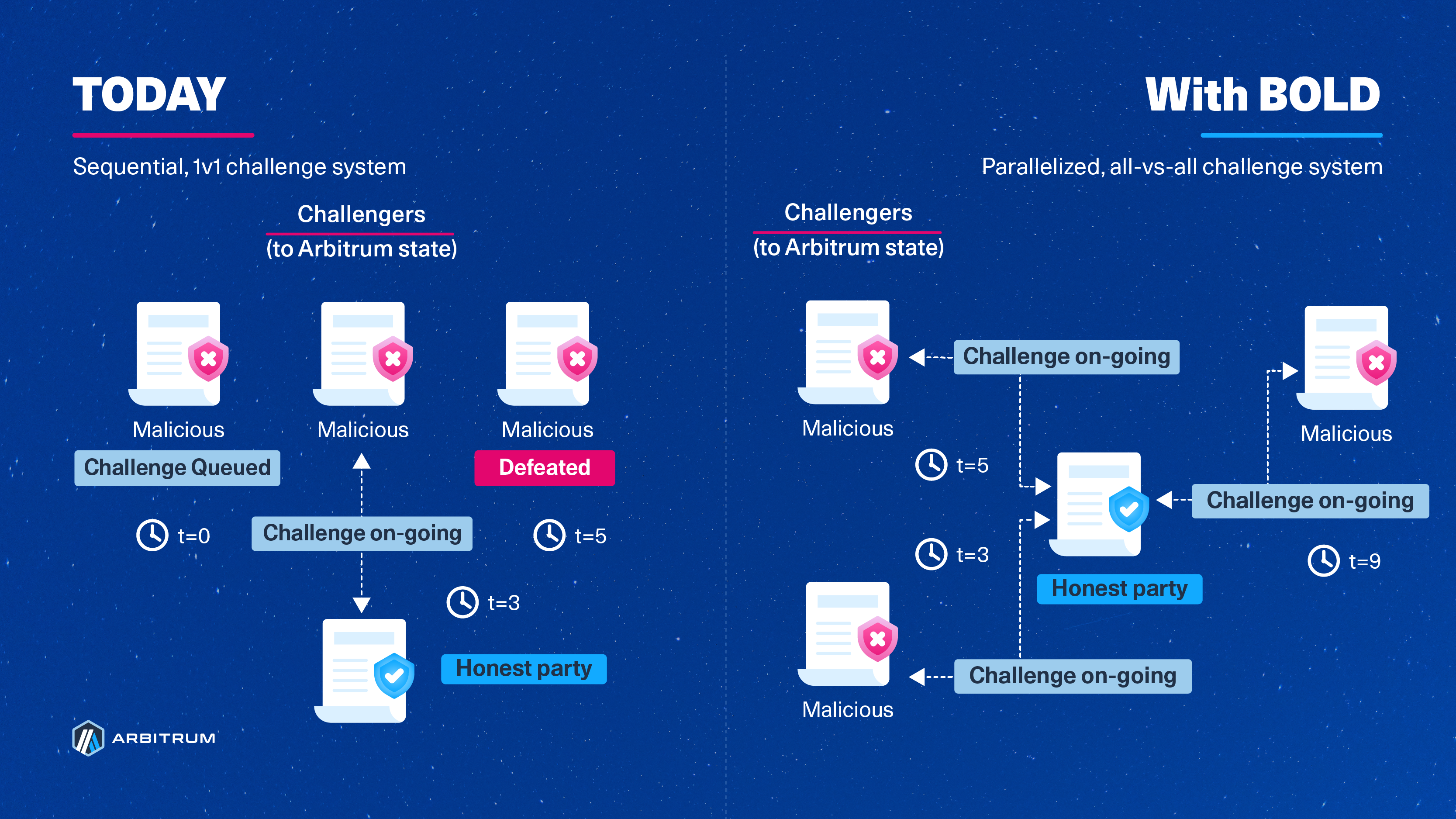

This challenge period is why you must wait ~1 week (6.4 days) to withdraw assets from Arbitrum One. While this design uses working fraud proofs for security, it is susceptible to delay attacks, where malicious actors continuously open disputes to extend that challenge period for as long as they’re willing to sacrifice bonds—effectively extending the challenge period indefinitely by an amount equal to the time it takes to resolve each dispute, one by one. This risk is not ideal nor safe, and is why validation for Arbitrum One and Nova was limited to a permissioned set of entities overseen by the Arbitrum DAO.

BoLD addresses these challenges head-on by introducing a time limit on the existing Rollup protocol for resolving disputes, effectively ensuring that challenges conclude within a 6.4-day window (the DAO can change this window for Arbitrum One and Nova). This conclusion is possible due to two reasons:

- BoLD’s design allows for challenges between the honest party and any number of malicious adversaries to happen in parallel, and

- The use of a time limit that will automatically confirm the honest party’s claims if the challenger fails to respond.

To summarize with an analogy and the diagram below: Arbitrum’s former dispute protocol assumed that any assertion that gets challenged must be defended against each unique challenger sequentially, like in a “1v1 tournament”. BoLD, on the other hand, enabled any single honest party to defend the correct state and guarantee a win, similar to an “all-vs-all battle royale” in which there must and will always be a single winner.

The timer/clocks above are arbitrary and instead represent the duration of challenges and the sequential nature of challenges today, but they can take place in parallel with BoLD. The durations of the challenges are independent of one another.

How is this possible?

The BoLD protocol provides the guardrails and rules for how validators challenge claims about the state of an Arbitrum chain. Since Arbitrum’s state is deterministic, there will always be only one correct state for a given input of onchain operations and transactions. The beauty of BoLD’s design ensures that disputes are resolved within a fixed time window, eliminating the risk of delay attacks and ultimately enabling anyone to bond their funds to and successfully defend the singular correct state of Arbitrum.

Let’s dive into an overview of how BoLD actually works.

- An assertion is made: Validators begin by taking the most recent confirmed assertion, called

Block A, and assert that some number of transactions afterward, using Nitro’s deterministic State Transition Function (STF), will result in an end state,Block Z. If a validator claims that the end state represented byBlock Zis correct, they will bond their funds toBlock Zand propose that state to its parent chain. (For more details on how bonding works, see Bold technical deep dive). If no one disagrees after a certain period, known as the challenge period, then the state represented by the assertionBlock Zis confirmed as the correct state of an Arbitrum chain. However, if someone disagrees with the end stateBlock Z, they can submit a challenge. - A challenge is opened: When another validator observes and disagrees with the end state represented by

Block Z, they can permissionlessly open a challenge by asserting and bonding capital to a claim on a different end state, represented by an assertionBlock Y. At this point, there are now two asserted states:Block A → Block ZandBlock A → Block Y. Each of these asserted states, at this point, is referred to as an edge, while a Merkle tree of asserted states from some start to endpoint (e.g.,Block A → Block Z) is more formally known as a history commitment. It is important to note that Ethereum at this point has no notion of which edge(s) are correct or incorrect - edges are simply a portion of a claim made by a validator about the history of the chain from some end state all the way back to some initial state. Also note that because a bond posted by a validator is for an assertion rather than for the party that posted it, there can be any number of honest, anonymous parties who can open challenges to incorrect claims. It is important to note that bonds posted to open challenges get held in the Rollup contract. There is a prescribed procedure outlining the Arbitrum Foundation's expectations regarding the use of these funds; see Step 5 below for a summary. - Multi-level, interactive dissection begins: To resolve the dispute, the disagreeing entities will need to agree on what the actual, correct asserted state should be. It would be tremendously expensive to re-execute and compare everything from

Block A → Block ZandBlock A → Block Y, especially since there could be potentially millions of transactions in betweenA,Z, andY. Instead, entities take turns bisecting their respective history commitments until they arrive at a single step of instruction, where an arbiter, such as Ethereum, can declare a winner. Note that this system is very similar to how challenges are resolved on Arbitrum chains today - BoLD only changes some minor, but important, details in the resolution process. Let’s dive into what happens next:- Block challenges: When a challenge gets opened, edges are referred to as level-zero edges since they are at the granularity of Arbitrum blocks. The disputing parties take turns bisecting their historical commitments until they identify the specific block on which they disagree.

- Big-step challenge: Now that the parties have narrowed down their dispute to a single block, the back-and-forth bisection exercise continues within that block. Note that this block is agreed upon by all parties to be a state that follows the initial state but precedes the final state. This time, however, the parties will narrow down on a specific range of instructions for the State Transition Function within the block - essentially working towards identifying a set of instructions within which their disagreement lies. Currently, this range is 2^20 steps of

WASMinstructions, which is the assembly of choice for validating Arbitrum chains. - One-step challenge: Within that range of 2^20 instructions, the back-and-forth bisecting continues until all parties arrive at a single step of instruction that they disagree on. At this point, the parties agree on the initial state of Arbitrum before the step, but disagree on the end state immediately after. Remember that since Arbitrum’s state is entirely deterministic, there is only one correct end state.

- One-step proof: Once a challenge is isolated down to a dispute about a single step, both parties run that step to produce, and then submit, a one-step proof to the OneStepProof smart contract on the parent chain (e.g., Ethereum). A one-step proof is a proof that a single step of computation results in a particular state. The smart contract on the parent chain will execute the disputed step to validate the correctness of the submitted proof from both parties. It is at this point that the honest party's proof will be deemed valid and its tree of edges will be confirmed by time, whereas the dishonest party's edges will be rejected due to a timeout.

- Confirmation: Once the honest one-step edge is confirmed, the protocol will work on confirming or rejecting the parent edges until it reaches the level-zero edge of the honest party. With the honest party’s level-zero edge now confirmed, their assertion bond is refundable. Meanwhile, the dishonest party has its bonds removed to ensure that dishonesty is always punished.

- There is another way that a level-zero edge can get confirmed: time. At each of the mini-stages of the challenge (block challenge, big-step challenge, one-step challenge), a timer increments upwards towards some challenge period, T, defined by BoLD. This timer begins ticking for a party when they submit their bisected history commitment, and it continues until their challenger submits their bisected history commitment in response. An edge is automatically confirmed if the timer reaches T.

- Reimbursements for the honest party's parent chain gas costs and mini-bonds made at the other challenge levels are handled by the Arbitrum Foundation.

That’s it! We’ve now walked through each step that validators will take to dispute challenges under the BoLD protocol. One final note is that each of the steps explained above can run concurrently, which is one of the reasons why BoLD can guarantee a resolution to disputes within a fixed time frame.

Frequently asked questions about BoLD (FAQ):

Q: How does bonding work?

The entities responsible for posting assertions about Arbitrum state to Ethereum are called validators. If posting assertions were free, anyone could create conflicting assertions at will to delay withdrawals by 14 days instead of 7. As such, Arbitrum requires validators to put in a “security deposit”, known as a bond, to be allowed to post assertions. Validators can withdraw their bond as soon as their latest posted assertion receives confirmation, and they will then end their responsibilities. These bonds can be any ERC-20 token. They should be set to a large enough value (e.g., 200 WETH) to make it economically infeasible for an adversary to attack an Arbitrum chain and to mitigate against spam (that would otherwise delay confirmations). Requiring a high bond to post assertions about Arbitrum seems centralized, as we are replacing an allowlist of validators with a system that requires a large financial commitment to participate. To address this, there is a contract that anyone can use to deploy a bonding pool as a way of crowdsourcing funds from others who wish to help defend Arbitrum but who may not individually be able to put up the large upfront bond itself. The use of bonding pools, coupled with the fact that there can be any number of honest anonymous parties ready to defend Arbitrum, means that these high bond values do not harm decentralization.

Q: Why are the bond sizes so high for Arbitrum One?

There are two types of “bonds” in BoLD: assertion and challenge. The sizes below are carefully calculated and set for Arbitrum One, using a variety of factors, including TVL, to optimize a balance between the cost for honest parties and the security of the protocol. As always, the exact bond sizes for an Arbitrum chain using BoLD is entirely up to the chain owner to decide, if they choose to adopt BoLD at all.

Assertion bond sizes

Assertion bond sizes are akin to a “security deposit” that an entity deposits to fulfill the role of a proposer (i.e., a validator who proposes state assertions to the parent chain). The bond sizes are high because the proposer assumes significant responsibility: they must ensure the chain progresses. Accordingly, the bond also acts as a deterrent to delay attacks, where the attacker would sacrifice the bond to cause roughly a week of delay in a group of withdrawals. If the bond is too small or free, there may not be sufficient deterrence against this type of attack. Validators who choose to be proposers can withdraw their bond as soon as the protocol has confirmed their most recent posted assertion. We expect there to be very few proposers for Arbitrum One, as only one is sufficient for the chain's safety and full functionality.

Challenge bond sizes

If someone disagrees with a posted assertion from a proposer, they can pool funds together to propose their assertion that represents the correct history of the chain. Upon doing so, a challenge between the two claims will begin. Anyone can participate in the challenge, as it is permissionless. To resolve a challenge, participants will incur compute and gas costs due to the interactive fraud proof game. Additionally, certain moves within a challenge require an extra bond to prevent resource exhaustion and spam from adversaries. These moves within a challenge require smaller, challenge bonds. The proposed challenge bonds for Arbitrum One are 1,110 ETH to fully resolve a dispute, which will also be reimbursed upon confirmation of the protocol's assertions.

The rationale for the specific challenge bond size is based on a concept known as a “resource ratio,” defined as the cost ratio between an adversary and an honest party when participating in the interactive fraud-proof game. Selecting this value ensured that the malicious party would pay 10 times the honest party's marginal costs. This resource ratio, coupled with the fact that an honest party will always have its bonds refunded while a malicious party loses everything, helps prevent and deter attacks from the outset.

To summarize with a scenario, this effectively means that defending against a $1B dollar attack would require ~$100M of bonds. The ~$100M would be reimbursed upon winning a challenge, while the $1B in bonds posted by an adversary would be forfeited. The proposal aims to send the confiscated funds to the treasury by setting the “excess state receiver” address to the DAO’s treasury address. The trade-off is that the higher the resource ratio we want, the more expensive it is for both honest and dishonest parties to make claims in disputes.

Bonding pools as a way to allow people to participate in assertion posting

BoLD ships with trustless bonding pools that allow any group of participants to pool their funds together to challenge a dishonest proposer, and win. That is, any group of entities can pool funds into a simple contract that will post an assertion to Ethereum without needing to trust each other. Upon observing an invalid assertion, validators have a challenge period (~6.4 days) to pool funds in the contract and respond with a counterassertion. Making it easy to pool the funds to participate in the defense of the Arbitrum trustlessly improves decentralization and the safety of BoLD.

Q: Does the bond requirement only mean that whales can validate Arbitrum One?

Validating Arbitrum One is free and accessible. By default, all Arbitrum One nodes are watchtower validators, meaning they can detect and report invalid assertions posted to Ethereum.

However, becoming an assertion proposer requires a bond, as without it, anyone could delay all Arbitrum-bridged assets by one week. However, BoLD allows anyone to propose assertions and also challenge invalid assertions via pool contracts, helping keep proposers accountable for their actions.

Q: How does BoLD disincentivize malicious actors from attacking an Arbitrum chain?

Honest parties will always be refunded, while malicious actors will always stand to lose 100% of their bond. Malicious actors stand to lose everything at each challenge. The BoLD delay is bounded, and additional challenges would not increase the delay of a particular assertion.

Q: In the event of a challenge, what happens to the confiscated funds from malicious actors for Arbitrum One?

Recall that BoLD enables any validator to put up a bond to propose assertions about the child chain state. These assertions about the child chain state are deterministic, so an honest party who posts a bond on the correct assertion will always win in disputes. In these scenarios, the honest party will eventually have their bonds reimbursed while the malicious actor will lose all of their funds.

In BoLD, all costs spent by malicious actors are confiscated and sent to the Arbitrum DAO treasury. A small reward, called the Defender's Bounty, of 1% will go to entities who put down challenge bonds in defense of Arbitrum One. For the remaining funds, the Arbitrum DAO will have full discretion over how to use those confiscated from a malicious actor. Applications include, but are not limited to:

- Using the confiscated funds to refund the parent chain gas costs to honest parties,

- Rewarding or reimbursing the honest parties with some, or all, of the confiscated funds over the 1% Defender's Bounty,

- Burning some, or all, of the confiscated funds, or

- Keep some, or all, of the confiscated funds within the Arbitrum DAO Treasury

As always, an Arbitrum chain can choose how it wishes to structure and manage confiscated funds from dishonest parties.

Q: Why are honest parties not automatically rewarded with confiscated funds from a malicious actor?

It’s tempting to think that rewarding the honest proposer in a dispute can only make the protocol stronger, but this turns out not to be true, because an adversary can sometimes profit by placing the honest bonds themselves.

This situation creates perverse incentives that threaten BoLD's security. Here’s an example, from Ed Felten:

That said, there’s no harm in paying the honest proposer a fair interest rate on their bond, so they don’t suffer for having helped the protocol by locking up their capital in a bond.

Therefore, the BoLD AIP proposes that honest parties be rewarded with 1% of the bonds confiscated from a dishonest party in the event of a challenge. This reward applies only to entities that deposit challenge bonds and participate in defending Arbitrum against a challenge. The exact amount rewarded to honest parties will be proportional to the amount the defender deposits into the protocol during a challenge, making bonding pool participants eligible.

Q: Why is ARB not the bonding token used for BoLD on Arbitrum One?

Although BoLD supports using an ERC-20 token, Ethereum, specifically WETH, was chosen over ARB for a few reasons:

- Arbitrum One and Arbitrum Nova both inherit their security from Ethereum already. Arbitrum One and Nova rely on Ethereum for both data availability and as the referee for determining winners during fraud-proof disputes. Ethereum’s value is also relatively independent of Arbitrum, especially when compared to

ARB. - Adversaries might be able to exploit the potential instability of

ARBwhen trying to win challenges. Suppose an adversary deposits their bond inARBand can create an impression that they have a nontrivial chance of winning the challenge. This impression might drive down the value ofARB, which would decrease the adversary's cost to create more bonds (i.e., more spam) during the challenge, which in turn could increase the adversary's chances of winning (which would driveARBlower, making the attack cheaper still for the adversary, etc.). - Access to liquidity: Ethereum has greater liquidity than

ARB. In the event of an attack on Arbitrum, access and ease of pooling funds may become crucial. - Fraud proofs are submitted to, and arbitrated on, the parent chain (Ethereum). The bonding of capital to make assertions is done so on the parent chain (Ethereum), since Ethereum is the arbitrator of disputes. If BoLD were to use

ARBinstead of Ethereum, a large amount ofARBmust be pre-positioned on the parent chain, which is more difficult to do when compared to pre-positioning Ethereum on the parent chain (Ethereum).

An Arbitrum chain owner may choose to use any token they wish for bonding if they adopt and use BoLD permissionless validation.

Q: Can the required token for the validator be set to ARB, and can network ETH revenues get distributed for validator incentives for Arbitrum One?

Yes. The asset a validator uses to become a proposer in BoLD can be configured to any ERC-20 token, including ARB. For Arbitrum One, ETH is used as a bond for various reasons mentioned above. The Arbitrum DAO can change this asset type at any time via a governance proposal. Should such an economic incentive model exist, the source and denomination of funds used to incentivize validators will be at the discretion of the Arbitrum DAO. Again, though, we don't see ARB-based bonding as a good idea at present; see the last question.

Q: How are honest parties reimbursed for bonding their capital to help secure Arbitrum One?

The Arbitrum DAO reimburses “active” proposers with a fair interest rate, as a way of removing the disincentive to participate, by reimbursing honest parties who bond their capital and propose assertions for Arbitrum One. The interest rate should be denominated in ETH and should be equal to the annualized yield that Ethereum mainnet validators receive, which at the time of writing, is an APR between 3% to 4% (based on CoinDesk Indices Composite Ether Staking Rate (CESR) benchmark and Rated.Network). This interest is considered a reimbursement because this payment reimburses the honest party for the opportunity cost of locking up their capital and should not be perceived as a “reward” - for the same reasons why the protocol does not reward honest parties with the funds confiscated from a malicious actor). These reimbursement payments can be paid out upon an active proposer’s honest assertion being confirmed on Ethereum and will be calculated and handled offchain by the Arbitrum Foundation.

BoLD makes it permissionless for any validator to become a proposer and introduces a way to pay service fees to honest parties for locking up capital to do so. Validators are not considered as active proposers until they successfully propose an assertion with a bond. To become an active proposer for Arbitrum One post-BoLD, a validator must propose a child chain state assertion to Ethereum. If they do not have an active bond on the parent chain, they need to attach a bond to their assertion to post it successfully. Subsequent assertions posted by the same address will move the already-supplied bond to their latest proposed assertion. Meanwhile, if an entity, say Bob, has posted a successor assertion to one previously made by another entity, Alice, then Bob would be considered the current active proposer by the protocol. Alice will no longer be considered the active proposer by the protocol, and once her assertion is confirmed, she will receive a refund of her assertion bond. There can only be one “active” proposer at any point in time.

The topic of economic and incentive models for BoLD on Arbitrum One is valuable. It deserves the full focus and attention of the community via a separate proposal or discussion, decoupled from this proposal to bring BoLD to mainnet. Details regarding proposed economic or incentive models for BoLD will require ongoing research and development. However, deploying BoLD as-is represents a substantial improvement to Arbitrum's security, even without addressing economic-related concerns. The DAO may, through governance, choose to fund other parties or modify this reimbursement model at any time.

For Arbitrum chains, any economic model can be configured alongside BoLD if chain owners decide to adopt BoLD.

Q: For Arbitrum One proposers, is the service fee applied to the amount bonded? If that’s the case, the ETH would be locked and thus unable to be used to generate yield elsewhere. So, which assets get used to create this yield for the service fee? Would it involve some ETH from the Arbitrum bridge?

The proposed service fee should correlate to the annualized income that Ethereum mainnet validators receive over the same period. At the time of writing, the estimated annual income for Ethereum mainnet validators is approximately 3% to 4% of their bond (based on CoinDesk Indices Composite Ether Staking Rate (CESR) benchmark and Rated.Network).

The fee is applied to the total amount bonded over the duration of a proposer's activity. A validator must deposit ETH into the contracts on the parent chain to become a proposer. So those deposited funds will indeed be unable to be used for yield in other scenarios. The decision on the source of funds for the yield is entirely up to the ArbitrumDAO.

Q: For Arbitrum One, will the offchain computation costs get reimbursed? (i.e., the costs for a validator computing the hashes for a challenge)

Reimbursements will not be made for any offchain computation costs, as we view these as costs borne by all honest operators, alongside the maintenance and infrastructure costs that regularly arise from running a node.

Our testing has demonstrated that the cost of running a sub-challenge in BoLD, the most computationally-heavy step, on an AWS r5.4xlarge EC2 instance, costs around USD $2.50 (~$1 hour for one challenge with 2.5 hour duration) using on-demand prices for U.S. East (N. Virginia). Therefore, the additional costs from offchain compute are assumed to be negligible relative to the regular infra costs of operating a node.

Q: How will BoLD impact Arbitrum Nova?

Although this AIP proposes that both Arbitrum One and Nova upgrade to use BoLD, we recommend the removal of the allowlist of validators for Arbitrum One while keeping Nova permissioned with a DAO-controlled allowlist of entities - unchanged from today.

This decision comes from two reasons: First, Arbitrum Nova’s TVL is much lower than Arbitrum One’s TVL (~$17B vs. ~$46M at the time of writing, from L2Beat). This lower TVL means that the high bond sizes necessary to prevent spam and delay attacks would comprise a significant share of Nova’s TVL, which we believe introduces a centralization risk, as very few parties would have an incentive to secure Nova. A solution here would be to lower the bond sizes, Second, the lower bond sizes increase the cost of delaying griefing attacks (where malicious actors delay the chain’s progress) and thereby undermine the chain's security. We believe enabling permissionless validation for Nova is not worth the capital requirement trade-offs, given the unique security model of AnyTrust chains.

Notably, since Arbitrum Nova's security already depends on at least one DAC member providing honest data availability, trusting the same committee to have at least one member provide honest validation does not add a major trust assumption. This trust assumption requires all DAC members to run validators as well. If the DAC is also validating the chain, a feature the Offchain Labs team has been working on, Fast Withdrawals, would allow users to withdraw assets from Nova in ~15 minutes, or the time it takes to reach parent chain finality. This finality is made possible by the DAC, which attests to and instantly confirms an assertion. Fast Withdrawals will be the subject of a future forum post and snapshot vote.

Q: When it comes to viewing the upfront assertion bond (to be a proposer) as the security budget for Arbitrum One, is it possible for an attacker to go above the security budget, and if so, what happens then?

The upfront capital to post assertions (onchain action) is 3,600 ETH, with subsequent sub-challenge assertions requiring 555/79 ETH (per level). This cost applies to both honest proposers and malicious entities. A malicious entity can post multiple invalid top-level assertions and/or open multiple challenges, and the honest entity can

It is critical to note that Arbitrum state transitions are entirely deterministic. An honest party bonded to the correct state assertion will receive all their costs refunded, while a malicious entity stands to lose everything. Additionally, BoLD’s design ensures that any party bonded to the correct.

If a malicious entity wanted to attack Arbitrum, they would need to deposit 3600 ETH to propose an invalid state assertion.

- Anyone can run an Arbitrum node (today and post-BoLD)

- The default mode is

watchtower, which chills out and watches the chain in action. It will alert you if it detects something wrong on the chain, but it takes no action. It requires no funds and doesn't take any onchain action. - Other "modes" that nodes can run are:

stakeLatest,resolveNodes,makeNodes, anddefensive. All of these modes require funds and will take onchain action.- Nodes running in this mode are considered validators because they validate what they see and take onchain action.

- Running a

watchtowernode is not a validator. - Proposers are in a special role; they strictly run in

makeNodesmode. This role means a proposer is someone running an Arbitrum node inmakeNodesmode, also making them a validator. - For more information about see Running a Node and Validation strategies.

Q: How do BoLD-based L3s challenge periods operate, considering the worst-case scenario?

To recap, both Arbitrum’s current dispute protocol and BoLD require assertions to be posted to the parent chain and employ interactive proving, which involves a back-and-forth between two entities until a single step of disagreement is reached. That single disputed step then gets submitted to contracts on the parent chain, which will eventually declare a winner. For L2s such as Arbitrum One, BoLD must be deployed on a credibly neutral, censorship-resistant backend to ensure fair dispute resolution. Ethereum is therefore the ideal candidate for deploying the BoLD protocol on L2s.

But you might now be wondering: what about L3 Arbitrum chains that don’t settle to Ethereum? Unlike L2s that settle to Ethereum, assertions on an L3’s state need to be posted to an L2 either via (A) the L3 Sequencer or (B) the Delayed Inbox queue managed by the L2 sequencer on L2. If the parent chain (in this case, L2) is getting repeatedly censored or if the L2 sequencer is offline, every block-level assertion and/or sub-challenge assertion would need to wait 24 hours before they can bypass the sequencer (using the theSequencerInbox’s forceInclusion method described here). If this were to happen, challenge resolution would get delayed by a time t where t = (24 hours) * number of moves for a challenge. To illustrate with sample numbers, if a challenge takes 50 sequential moves to resolve, then the delay would be 50 days!

To mitigate the risk of this issue manifesting on Arbitrum chains, Offchain Labs has included a feature called Delay Buffer in BoLD’s 1.0.0 release. The Delay Buffer feature aims to limit the negative effects of: prolonged parent chain censorship, prolonged sequencer censorship, and/or unexpected sequencer outages. This buffer is configurable by setting a time threshold that decrements when unexpected delays occur. Once that time threshold is reached, the force inclusion window is reduced, effectively allowing entities to make moves without the 24-hour delay per move.

Under reasonable parameterization, the sequencer could be offline/censoring for 24 hours twice, before the force inclusion window drops from 24 hours to a minimum inclusion time. The force inclusion window gradually (over weeks) replenishes to its original value over time as long as the sequencer is on "good behavior" - regularly sequencing messages without unexpected delays. We believe that the Delay Buffer feature provides stronger guarantees of censorship resistance for Arbitrum chains.

The methodology for calculating the parameters, specifically for L3 Arbitrum chains, will be made available at a later date for teams who wish to use BoLD.

Q: What is the user flow for using the assertion bonding pool contract?

The autopooling feature is not available on Arbitrum Nitro as of yet.

Anyone can deploy an assertion bonding pool using AssertionStakingPoolCreator.sol as a means to crowdsource funds to put up a bond for an assertion. To defend Arbitrum using a bonding pool, an entity would first deploy this pool with the assertion they believe is correct and wish to put up a bond to challenge an adversary's assertion. Then, anyone can verify that the claim is correct by running the inputs through their node's State Transition Function (STF). If other parties agree that the assertion is correct, then they can deposit their funds into the contract. When sufficient funds are available, anyone can permissionlessly trigger the creation of the assertion onchain to initiate the challenge. Finally, once the dispute protocol confirms the honest parties' assertion, all involved entities can receive reimbursement for their funds and withdraw. The Arbitrum Nitro node validation software also features an optional "auto pooling" option that automates the entire workflow for assertion bonding pool deployment and depositing funds into the pool. If "auto pooling" is activated and the private key controlling the validator has sufficient funds, a trustless pool will get deployed alongside an assertion of the available funds. If a validator with the "auto pooling" feature enabled sees an assertion onchain that it agrees with and a bonding pool already exists for that assertion. The validator will automatically deposit funds into the bonding pool to "join" others backing that onchain assertion in a trustless manner.

Q: What type of hardware will be necessary to run a BoLD validator?

The minimum hardware requirements for running a BoLD validator are still being researched and finalized. The goal, however, is that regular consumer hardware (i.e., a laptop) can effectively secure an Arbitrum chain using BoLD in the average case, by any honest party.

Q: How do BoLD validators communicate with one another? Is it over a P2P network?

BoLD validators for Arbitrum chains communicate directly with smart contracts on the parent chain (Ethereum), meaning that opening challenges, submitting bisected history commitments, one-step proofs, and confirmations are all adjudicated on the Ethereum blockchain. There is no P2P between validators.

Q: For an L3 Arbitrum chain, secured using BoLD, that settles to Arbitrum One, does the one-step proof happen on the parent chain?

Yes, it happens on Arbitrum One.

Q: For Arbitrum One, does implementing BoLD reduce the scope or remove the need for the Arbitrum Security Council?

BoLD can limit the scope of Arbitrum One and Nova’s reliance on the Security Council as it takes Arbitrum chains one step closer to complete decentralization.