Inside Arbitrum Nitro

Transaction processing journey on Arbitrum

As a developer initiating a transaction on Arbitrum, gaining a clear understanding of the end-to-end flow—from initial submission through to finality—is helpful, but it is not required.

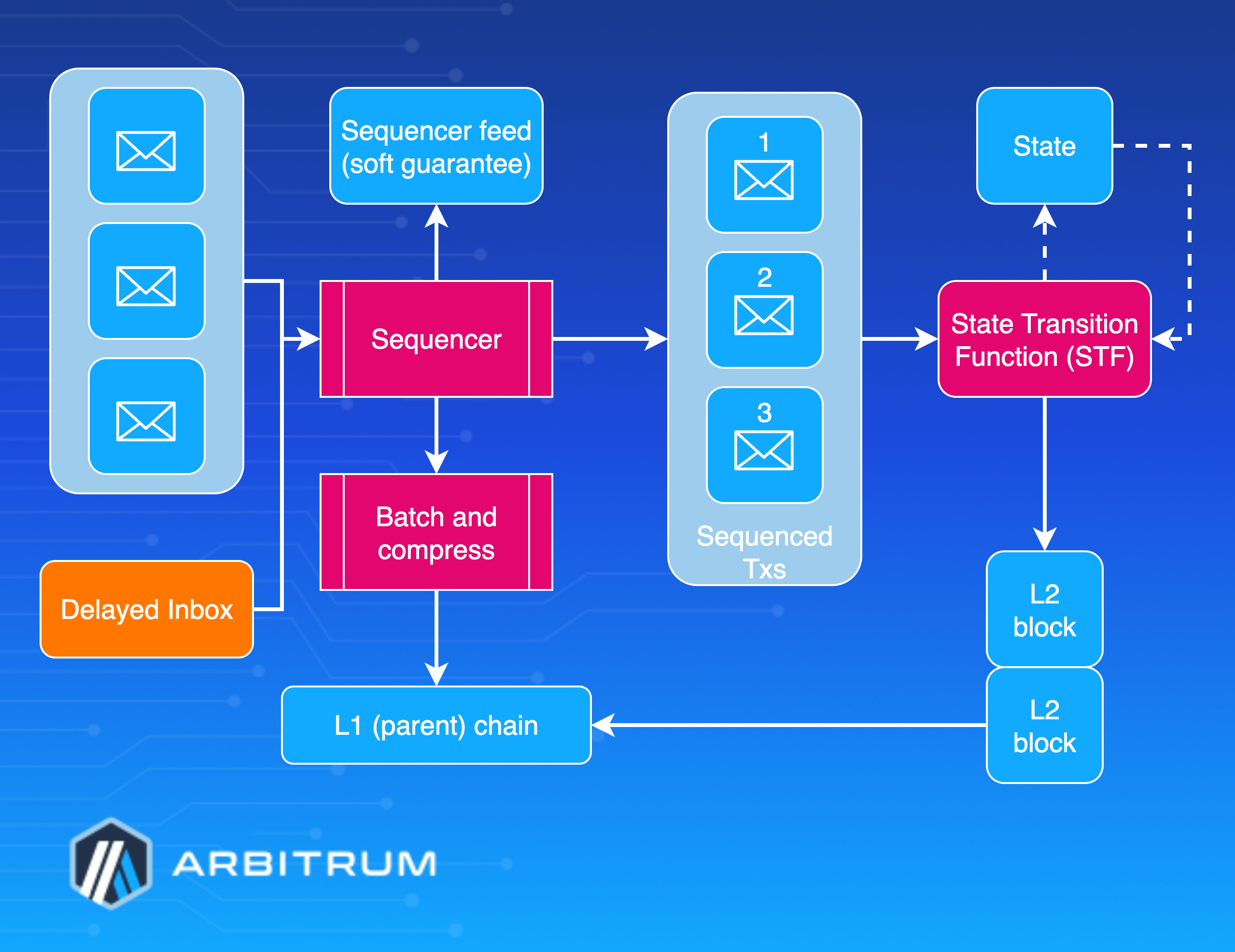

This overview methodically traces the transaction lifecycle, emphasizing how Arbitrum's architecture ensures precise, efficient, and secure handling at every stage. This article encompasses the complete Arbitrum Nitro stack, beginning with the Sequencer responsible for transaction ordering, advancing to the State Transition Function for execution, and culminating in validation mechanisms that uphold integrity.

Transaction lifecycle

Along the way, we will highlight Arbitrum's ability to deliver security on par with Ethereum, while achieving fee reductions by a factor of ten and transaction speeds accelerated by a factor of 100 through optimized scaling techniques.

The Foundation: Arbitrum's core architecture overview

Before delving into the journey of a transaction, it is important to outline the foundational architecture that powers Arbitrum's operations. Central to the architecture is a simple yet powerful principle: deterministic state transitions, which ensure consistent outcomes across the network. The system revolves around three core components.

Transactions first enter through the Inbox, serving as the primary gateway into the ecosystem. From there, the State Transition Function (STF) processes them in a deterministic fashion, applying rules that guarantee reproducibility. Finally, the Outputs component generates the resulting data and state updates, completing the cycle. This deterministic model means that identical inputs always produce the same outputs among honest nodes, forming the bedrock of Arbitrum's security. It supports efficient fraud proofs and dispute resolution, allowing verification of execution correctness without the need to rerun entire transactions, thereby minimizing computational overhead. For foundational concepts about the STF, see the State Transition Function gentle introduction.

Step 1: Submitting a transaction

The submission process for a transaction on Arbitrum starts with the user sending the request, with options tailored to balance factors like speed, control, and reliability according to specific needs. Most transactions route through the Sequencer, a specialized node that orders them and issues quick confirmations. This path accommodates various submission methods, including public RPC for development and light usage, third-party RPC for improved throughput, direct Sequencer endpoints for minimal latency in critical operations, and self-hosted Arbitrum nodes for ultimate privacy and customization.

Alternatively, to counter risks of exclusion or delay by the Sequencer, users can submit directly to the Delayed Inbox contract on Ethereum, bolstering system resilience. In this mechanism, non-Sequencer transactions enter a dedicated queue, where a well-functioning Sequencer typically integrates them within about ten minutes. If delayed beyond 24 hours, any network participant can force inclusion into the main inbox, limiting the Sequencer's influence to temporary delays rather than permanent blocks. While the Sequencer route offers faster soft finality and streamlined workflows, the Delayed Inbox path doubles processing time but emphasizes censorship resistance. Overall, the Sequencer's commitment to ordered inclusion provides "soft finality" for a responsive experience, complemented by these alternatives for robust, flexible operations across applications. For more technical detail about the transaction lifecycle, refer to the Transaction Lifecycle deep dive.

Step 2: Ordering and broadcasting: The Sequencer

Once a transaction reaches the Sequencer, it integrates into a refined system for ordering and broadcasting, designed to maximize performance while upholding security. The Sequencer immediately shares the transaction through its real-time feed, offering instant network-wide visibility. This feed delivers immediate confirmation of acceptance and sequencing, keeps all nodes synchronized with the latest order, and enables soft finality, allowing users to proceed confidently based on the Sequencer's reliable commitment. For comprehensive details on the Sequencer's operations, including sequencing, batching, compression, and censorship resistance, see the Sequencer deep dive.

To further optimize, the Sequencer groups transactions into batches rather than processing them individually, which cuts costs and boosts efficiency. Batches form when transactions accumulate to a predefined size or after a set time interval to prevent lags. The data then undergoes compression via the Brotli algorithm, with levels dynamically adjusted from 0 to 11 based on congestion. Higher compression reduces Layer 1 posting expenses at the cost of more computation, while the system shifts toward speed during heavy backlogs.

After batching and compression, the data posts to Ethereum through the Sequencer Inbox Contract using one of two methods.

-

The default, blob transactions under EIP-4844, provide cost-effective and scalable data inclusion when supported by Ethereum.

-

As a fallback, calldata transactions embed data directly, ensuring compatibility even if blob fees rise or EIP-4844 is unavailable. This process yields 10-100x cost savings over individual postings and adapts to network conditions for consistent efficiency. For details on how parent chain costs are calculated and priced, including the adaptive pricing algorithm, see the Parent chain pricing deep dive.

Step 3: Execution phase: State Transition Function

With ordering and batching complete, execution shifts to the State Transition Function (STF), the core of Arbitrum's processing engine. For foundational concepts about how the STF works, see the State Transition Function gentle introduction. Arbitrum ensures full Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) compatibility via a three-layer architecture. At the base, the Geth core handles EVM execution, aligning behaviors with Ethereum and drawing on its extensively tested code for security. For more technical details about Geth, refer to the Geth deep dive documentation.

Above this, ArbOS—the Arbitrum Operating System—adds Layer 2 features like cross-chain messaging, fee management, gas pricing, handling of deposits and withdrawals, and advanced tools such as Stylus. The top layer, the node interface, manages RPC connections and APIs, providing Ethereum-like functionality for clients.

In the STF, transactions follow a structured workflow: ArbOS first validates format and funds, then charges gas for Layer 2 execution and Layer 1 posting. Geth executes per EVM standards, after which ArbOS updates states and cross-chain elements, generating receipts and logs to conclude the process. For technical details about ArbOS, refer to the ArbOS deep dive documentation.

For Stylus contracts using WebAssembly (WASM), execution diverts to a WASM runtime, where contracts access state via specialized host I/O calls. This diversion yields 10-70x faster performance than EVM equivalents and full interoperability for mixed calls. The Geth base lets Ethereum apps run unchanged, while ArbOS and Stylus enable Layer 2 optimizations and high-performance innovations. Consult the State Transition Function deep dive for further mechanics.

Step 4: Finality

At this stage, the transaction achieves two complementary levels of finality, each tailored to Arbitrum's security needs.

-

Soft finality emerges immediately upon the inclusion of the Sequencer feed, offering instant acceptance feedback, a commitment to order, and the ability to act without wait times—as noted in the submission phase. This soft finality" relies on the Sequencer's trustworthiness for usability but lacks cryptographic backing.

-

Hard finality, conversely, solidifies when the batch posts and confirms on Ethereum, inheriting its consensus security, ensuring public data availability, and making the transaction irreversible. This process typically spans 10-20 minutes, varying with Ethereum block times and batch frequency. Hard finality depends on rollup assertions being confirmed on Ethereum; for more on how assertions work, see the Assertions deep dive.

The dual model combines rapid soft finality for seamless experiences with Ethereum-level safeguards for hard finality, along with censorship-resistant paths for assured inclusion. This balance delivers quick feedback alongside strong protections, ideal for high-stakes transactions.

Step 5: Ensuring correctness: Validation and dispute resolution

Following execution, Arbitrum verifies correctness through its validation and dispute systems. Central to this is the BoLD (Bounded Liquidity Delay) protocol, an advanced dispute framework enabling permissionless validation. Unlike conventional optimistic rollups, BoLD permits any participant to validate without approval, while ensuring dispute resolution within bounded timeframes to prevent indefinite delays.

BoLD facilitates a challenge-based defense where honest parties can protect the chain's state against malice. Disputants narrow conflicts to a single execution step via supporting claims, culminating in a one-step proof (OSP) that Ethereum verifies as an impartial arbiter to determine the outcome. While BoLD's intricacies—such as its multi-round challenge games and economic incentives—are extensive, they enhance decentralization and resilience. Validation occurs through assertions submitted to the Rollup contract; for details on how assertions structure validation and disputes, see the Assertions deep dive. For an introduction to BoLD, see the BoLD Gentle Introduction; for technical implementation details, see the BoLD Technical Deep Dive; and for economic considerations, see the Economics of Disputes documentation.

Step 6: Bridging: Cross-chain communication

Many transactions involve asset or data transfers between Ethereum and Arbitrum, managed through secure bridging protocols. For Parent-to-Child messaging from Ethereum to Arbitrum, options include native token bridging for direct ETH deposits, ERC-20 transfers via the canonical bridge, or support for custom gas tokens. Retryable tickets enable atomic operations with guaranteed retries if execution fails, featuring predictable gas costs and a one-week validity period redeemable by anyone. Direct messaging handles signed EOA messages with verification or unsigned contract messages using address aliasing for security. See the Parent-to-Child messaging deep dive for details.

Parent-to-Child transfers from Arbitrum to Ethereum begin with message creation via ArbSys.sendTxToL1(), followed by inclusion in a rollup assertion, a 6.4-day challenge period, and manual Layer 1 execution by any party. Messages validate through Merkle proofs, persist indefinitely until executed, and require manual triggering due to Ethereum's constraints. For details on how rollup assertions work and their role in finality, see the Assertions deep dive. See the Child-to-Parent messaging deep dive documentation for more details on the messaging process.

The canonical bridge architecture comprises asset contracts on both chains, gateway pairs for specific logic, and routers to direct flows. Its security locks tokens on one layer while minting equivalents on the other, with a seven-day challenge period guarding withdrawals. This setup fosters seamless, unified interactions while safeguarding each chain's integrity.

Step 7: The Economics of execution: Gas and fees

Fees accumulate across the transaction lifecycle to fund processing and security. Arbitrum's dual-fee model separates child chain gas fees, which cover EVM computation and storage with EIP-1559-style dynamic pricing, adjusting for congestion, from Parent chain data fees (blobs or calldata). Parent chain data fees account for Ethereum data posting based on compressed batch contributions and apply only to Sequencer submissions. For comprehensive details on how parent chain pricing works, including the adaptive pricing algorithm and cost apportionment, see the Parent chain pricing deep dive. For a complete breakdown of how fees are calculated and collected, including both parent and child chain components, refer to the Gas and fees deep dive.

A gas target is an optimal gas consumption rate/second. Exceeding this rate triggers EIP-1559 fee escalations to prevent node overloads and maintain liveness. This rate prioritizes high-value transactions during peaks while deterring spam, ensuring that validators and the Sequencer stay operational, even though parent contracts handle ultimate security. You can read more about how the child chain gas fees are calculated in this explainer

Fee calculation during execution involves assessing child chain gas via EVM standards, estimating parent chain batch impact, applying current pricing, and collecting ETH totals. This model covers all costs effectively, with the gas target reinforcing security by keeping validation in sync.

Step 8: Advanced features

Arbitrum extends beyond standard Layer 2 capabilities with features like Stylus, which supports smart contracts in languages such as Rust, C, and C++ via WASM. It offers 10-70x faster execution and 100-500x better memory efficiency than the EVM, with full interoperability for cross-calls. Stylus runs in a co-located WASM VM using host I/O for state access—details in the Stylus Gentle Intro.

Timeboost refines ordering to capture MEV for chain operators, protect users from attacks like front-running, reduce spam-related congestion, and allow customizable policies. Timeboost preserves fast block times (250ms default) while enabling MEV capture and user protection. For an introduction to Timeboost, see the Timeboost Gentle Introduction; for implementation details and usage instructions, see the How to Use Timeboost documentation; and for troubleshooting guidance, see the Timeboost Troubleshooting and FAQ pages.

AnyTrust provides cost-optimized data availability with a mild trust model, relying on a Data Availability Committee (DAC) of N members, where at least two are assumed honest. It uses BLS-signed Data Availability Certificates (DACerts) and falls back to Layer 1 posting if needed. Keysets define member keys and thresholds; DACerts include hashes, expirations, and signatures; and servers support various storage, such as local files or Amazon S3. The Sequencer sends batches to the committee, gathers signatures for DACerts, and posts them to Layer 1, defaulting to full data if the required signatures are not present. Ideal for low-cost apps like gaming, as in Arbitrum Nova—explore the AnyTrust protocol documentation.

Related topics

This overview covers the complete transaction journey through Arbitrum Nitro. For deeper exploration of specific topics, refer to the following resources:

Deep dives

- Transaction Lifecycle: Detailed transaction lifecycle from submission to finality

- Sequencer: How the Sequencer orders, batches, and posts transactions

- Parent Chain Pricing: Adaptive pricing algorithm for parent chain costs

- State Transition Function: Gentle Introduction: Foundational concepts of the STF

- Geth: Geth core and EVM compatibility

- ArbOS: Arbitrum Operating System features and capabilities

- State Transition Function Inputs: Message types and STF processing mechanics

- Assertions: Rollup assertions and validation structure

- Parent-to-Child Messaging: L1 to L2 messaging and bridging

- Child-to-Parent Messaging: L2 to L1 messaging and withdrawals

- Gas and Fees: Fee calculation and gas pricing models

- AnyTrust Protocol: Data availability committee and cost optimization

BoLD (Bounded Liquidity Delay)

- BoLD: Gentle Introduction: Overview of permissionless validation

Timeboost

- Timeboost: Gentle Introduction: MEV capture and transaction ordering